In the heart of America’s entertainment industry, these fires could become the most documented and costly landscape/structural blaze in human history. The Palisades fire in Los Angeles began as a faint column of smoke carried southwest on the stiff winter air. In January—a month when Southern California typically recovers from holiday festivities, not wildfires—the hills of Los Angeles ignited. The Palisades Fire quickly evolved into a full-fledged fire complex, tearing through the dry, dense vegetation bordering the city’s northern urban fringe and transgressing into its structures at will. The Santa Monica and Angeles Mountains, iconic due to their appearance in a century of film, television, and global media, now serve as the stage for a tragic, real-world narrative where climate-intensified fire meets urban and industrial planning.

The scars left by this fire extend beyond the visible. For those who evacuated, lost loved ones, or watched their surroundings burn, the trauma runs deep. Communities experience the destruction of property and a rupture of Palisades and Eaton's safety and connection to the land. A good friend from Fort McMurray, Alberta, reflecting on the aftermath of the 2016 wildfire, noted how visitors often measured the disaster’s impact by whether someone had lost their home. Yet this binary overlooks the broader, more insidious ways lives are disrupted—through displacement, smoke damage, economic instability, and the sudden disappearance of green forests. Severe fires don’t distinguish sharply between those affected and those untouched; their reverberations permeate entire communities.

Somewhere across the loss lies a truth—From the homes we build to the infrastructure we depend on, living in a material world ties our sense of safety and well-being to possessions and structures that climate-enhanced fire can so quickly erase. This paradox forces us to question what it means to coexist with nature in a way that prioritizes safety, emotional recovery, and ecological harmony.

These fires occurred in a season already marked by an alarming pattern: seven landscape fires have erupted in the Los Angeles conservation parks since September 13, 2024, yet many were minimally covered by international news. If you are not in the greater Los Angeles area, you see a narrow or select view of the area’s increasingly weird fire behaviour. This fire isn’t merely an anomaly; it exemplifies two centuries of escalating fire risks shaped by climate change, urban and industrial expansion, and the erosion of traditional land management practices.

Sydney’s 2018 Menai Fire burned fiercely during mid-autumn on the border of a conservation park and a suburban area, showcasing the unpredictability of an expanding fire season. In Athens, the 2023 Attica Fires reached the city's urban edge, highlighting the vulnerability of industrial-urban thresholds. Fort McMurray’s 2016 fire, “The Beast” in Canada, was an early-season blaze of catastrophic severity, starting in the forest, travelling through the urban service centre and back to the forest on the other side—an example of unstoppable firepower. Meanwhile, Hobart, Tasmania, remains an example of a city before fire, embodying Professor Bowman’s "time bomb" analogy, with fire-prone conditions accumulating unchecked. Christchurch in Aotearoa/New Zealand provides another example, where the treasured recreational area of the Port Hills faced similar risks, which broke the blue skies with columns of smoke in 2017 and 2024. Without a holistic approach that integrates urban planning with ecological stewardship, these thresholds will continue to pose significant dangers globally.

The familiar dry-season fire threat had arrived out of time, out of place. Underscoring Bowman’s assertion that human activities have extended fire seasons globally and conservation areas ringing cities like Los Angeles can act as ‘time bombs,’ their unchecked vegetation feeding fires exacerbated by climate change. Climate change and urban expansion have redefined the boundaries of fire risks, with anthropogenic pressures amplifying the frequency and intensity of these events. Trails often frequented by Angelenos seeking refuge from urban life became conduits for open flames, illuminating the profound challenge of reconciling urban development, industrial coarseness and separation with an ancient ecological reality. If you try to stamp out the fire, it comes rolling back again. That is as sure plants, lightening, and oxygen are. These fires reflect a systemic trajectory, where a century of urban expansion and ecological neglect have heightened fire risks and are part of the inertia of a human’s two million-year-old anthropogenic fire story.

It is time to put on the brakes.

Conservation Park Thresholds: Fire as a Keeper of Balance

Fire breathes and behaves like a living entity, feeding, expanding, expelling and evolving with the same air that sustains us. Its 420-million-year relationship with Earth’s biota underscores its complexity and importance in the planetary role and human evolution. A question I'm asked most often “What started the fire?” However, the more pressing question is... How did it spiral out of control? What is the region’s fire history, and what are ignition's broad and narrow contexts of fires spread?

U.S. cities have invested heavily in building and infrastructure fireproofing. Over the last century, catastrophic fires reshaped the approach to urban fire safety. The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire in 1911, which claimed 146 lives due to locked exits and poor safety measures, pushed cities to enforce fireproof stairwells and outward-opening doors. In 1942, Boston’s Coconut Grove Nightclub Fire tragically highlighted the dangers of flammable materials and inadequate exits, prompting stricter occupancy regulations and egress standards. Similarly, the 1958 Our Lady of the Angels School Fire in Chicago, where 95 lives were lost, underscored the need for school sprinklers, fire alarms, and fire-resistant materials.

These historical lessons underscore how U.S. cities fortified urban centres, creating fireproofed structures resilient to many modern threats of structural fire. However, the Los Angeles Fire Complex illustrates a challenge beyond traditional urban and rural fire management strategies because it lies in constructing nature reserves and parks on the city’s periphery, a design motif familiar to cities across the globe that developed at the same rate as the cities themselves. Naturalism pioneer Emile Zola asked this question in 19th C Paris: What role does green space play for the proletariat, and where is it placed amidst rapid population growth? His solutions fell on the ears of European influence when the world population by the end of the century was a mere 1.8 billion, as an advocate of green space on city perimeters rather than within the city.

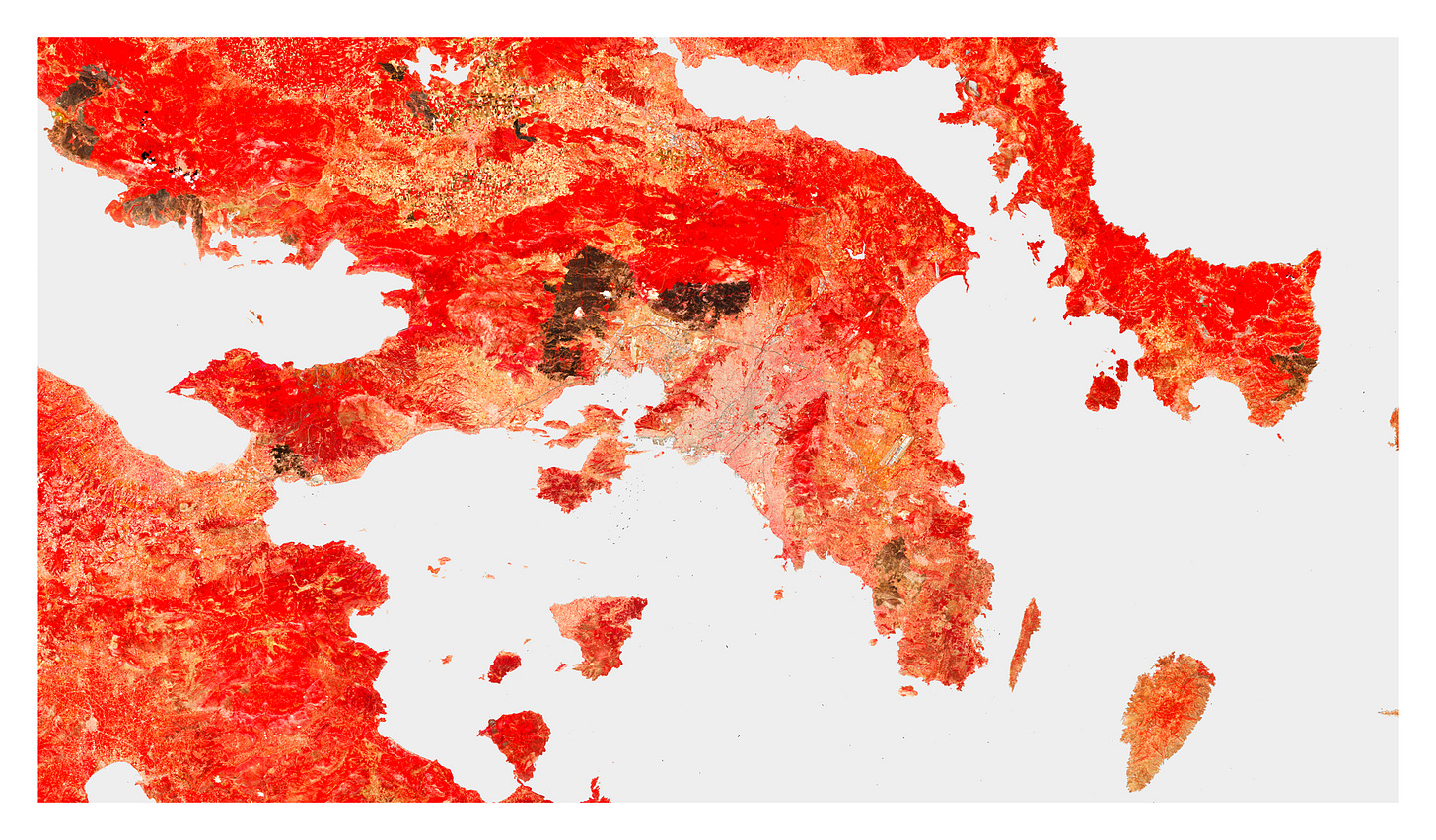

Threshold Fire | Athens/Attica, Greece 2021-2023

The mid-summer fires of 2021 and 2023 vividly demonstrated the vulnerability of the urban-industrial threshold to the slopes of the conservation area, the Parnitha mountain range. Fires skirted Athens’ perimeter, where the range distinctly intersects with populated areas. Walking through the aftermath, I observed blackened hillsides, a cleaning of plants and smouldering trees, and burnt homes, businesses and infrastructure in the blistering heat of the season. The proximity of these fires to the city underscored how vulnerable these urban/industrial thresholds have become, particularly during the peak of summer.

The Attica/Athens fires also revealed the role of suspicion, as thick as the smoke columns around ignition and fire management. In many cases, arson—whether driven by political gains or domestic or international terrorism—was highly suspected. The perception of the ignition is deliberate and that forests cleared by fire would soon be developed exacerbated tensions; the perception is not without evidence, with delayed emergency response coupled with landscape dominating wind turbines soon after the burns. Once the immediate threat to homes and lives had passed, firefighters prioritised containment over suppression, allowing flames to continue burning through woodlands. While pragmatic, given limited resources, this decision left behind a landscape vulnerable to urban and industrial development—altering the ecosystem and hindering natural recovery. While in the region, I experienced this suspicion firsthand as Fire besieged the town. It led to being captured by local militia and heavily questioned by Fire Inspectors at a Police Station for 4 hours; it could have been much longer.

Similar questions and emotions may arise for the people of Los Angeles, but if the ignition was deliberate, did they intend this extent of fire? Probably not. We must look at the broader context of fire and human behaviour, and fire raises a hard truth.

Early Recognition Time Bombs | Hobart Town/Lutruwita

Tasmanian bushland edges offer a perspective on how fire management strategies evolve—or stagnate—over time. Today, fire has largely been stamped out, leaving Hobart surrounded by a fuel-rich landscape primed for ignition. The unchecked vegetation growth in conservation areas, similar to those encircling cities like Los Angeles, can act as ‘time bombs,’ waiting for the right conditions to explode into catastrophic fire events.

In exploring these dynamics, I collaborated with Professor David Bowman, a leading pyrocologist at the University of Tasmania and one of the foremost experts on global fire ecology. His research has been instrumental in shaping contemporary understandings of fire’s role in ecosystems, particularly how anthropogenic influences—both historical and modern—have disrupted natural fire regimes.

Alongside Bowman, I worked with Dr. Julia Lum, an art historian specializing in the visual cultures of empire and the representation of landscape in colonial contexts. As an Associate Professor at Scripps College and a Getty/ACLS Postdoctoral Fellow in the History of Art (2023), Lum’s scholarship critically examines how colonial-era artists depicted—or deliberately omitted—Indigenous land management practices, particularly the use of fire as a tool for shaping the environment. Her research brings an essential perspective to studying fire history, revealing how 18th-century European aesthetic ideals influenced how landscapes were framed, understood, and later mismanaged. Julia’s Essay Fire-Stick Picturesque: Landscape Art and Early Colonial Tasmania, examines how fire shaped the hills surrounding the Derwent River over two centuries and how shifting attitudes toward fire are reflected in historical and contemporary imagery.

This research informed a 2019 artwork documenting changes in land and fire knowledge systems over time. Paintings by John Glover, for example, depict Tasmania’s rolling landscapes as untouched and pristine—erasing the reality of Indigenous fire management, which fostered biodiversity and mitigated catastrophic fire risks. Such practices contrast sharply with modern fire suppression strategies, which, rather than eliminating risk, have led to greater fire intensity by allowing fuel to accumulate unchecked.

The urgency of these insights became undeniable in 2020, when the Black Summer Fires devastated vast areas of Australia. That same year, I further collaborated with Bill Gammage, historian and author of The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia, to explore the contrast between fire-managed and fire-suppressed landscapes. We pieced together a diptych, drawing from Eugene von Guérard’s (1811–1901) painting Junction of the Buchan and Snowy Rivers, Gippsland and a modern, fire-scarred landscape. The juxtaposition is striking: on the left, trees shaped by centuries of Indigenous fire stewardship stand in open, resilient formation. On the right, a fire-fought forest—densely packed with fuel—has been ravaged by a full-blown crown fire, leaving skeletal remains of trees in its wake.

This visual contrast reinforces a hard truth: fire is not the enemy—it is a force to be engaged with intelligently. Indigenous land management once balanced fire as an ally, preventing today’s destructive wildfires. If we continue to fight fire with total suppression, we may find ourselves battling ever-worsening consequences.

Expanding Season | Menai, Sydney, Australia

An example of the Southern Hemisphere Fire in Australia's expanded fire season, the 2018 Menai Fire near Sydney, emphasises the prolonged fire seasons becoming increasingly unpredictable and lengthening. I witnessed how the dense vegetation of the Royal Parks on the fringe of a major city became a liability when fire sparks up out of the typical fire season. The blaze burned unusually intensely for mid-autumn conditions, creating high-intensity flames when fire crews had entered the winter phase of fire management, with much of their equipment packed away or returned to the northern hemisphere as part of an equipment-sharing agreement. Observing the aftermath, I camped there to observe the evaporated streams, blackened eucalyptus, acacia, and banksia alongside widespread fast-appearing epicormic ( new shoots out of the tree trunk) growth, showcasing the destructive force of fire and the resilience of fire-adapted Australian plants. However, the unseasonality of a hot 4,000-acre fire underscored the broader issue of shifting fire patterns due to climate change—a vivid reminder of the challenges posed by increasing unpredictability in fire behaviour.

Catastrophic | Fort McMurray, Alberta, Canada

For Fort McMurray, Alberta, Canada, in May 2016, a wildfire ‘The Beast’ forced the evacuation of 80,000 people in a single afternoon. Initially igniting on the outskirts, the fire breached the city’s perimeter and surged through its core, transforming from a severe forest fire into an urban inferno. Entire neighbourhoods were consumed as the fire exploited urban planning and construction vulnerabilities. A three-bedroom house could be reduced to ashes in 3 to 5 minutes, its destruction marking the fire’s terrifying speed and intensity.

The path of the fire was indiscriminate, ripping through residential areas seen above in the rebuilding of Waterways, with 95% of all structures lost; after leaving Fort McMurray, the blaze shimmered and cut its way east for another 30 days, spreading through the boreal forest for which is it well accustomed.

An Arab Spring for Fire

The Los Angeles Fires is unique because it has broached the edges of a major U.S. city and impacts a population rich with storytellers—writers, filmmakers, artists, and journalists—experiencing this tragedy firsthand. Hollywood, synonymous with disaster fiction and dystopian futures, now documents a catastrophic nonfiction reality -be careful about what you wish for. These narratives will undoubtedly shape global perceptions of wildfires, amplifying the issue's urgency.

This moment parallels the transformative power of historical events, where widespread access to storytelling tools enabled a global audience to witness and react to unfolding crises. Similarly, the Los Angeles Fires, occurring in a city deeply entwined with international media, is set to become one of history's most filmed and iconic burns. The sheer volume of footage, stories, and firsthand accounts emerging from this fire could redefine how society understands and addresses wildfires.

A Future We Can Shape

This year, I am returning to Fort McMurray with a book from the months after their fire; there will be a festival weekend to both celebrate and reflect. Then I'll carry on the work on Regenerative Fire, Fire as an ally. Our work is grounded in connecting, listening, acting, collaborating and understanding the differences that make one another. The aspect of big fires stays with me; it's the extent of trauma and loss nestled beside our benign capacity to love deeply when losses happen.

Fire emergencies like this also bring out the best of our humanity. They remind us of our capacity to gather, support, and care for one another in adversity. Stories of neighbours helping neighbours, strangers offering shelter, and communities uniting to rebuild exemplify the profound resilience and solidarity that emerge during such crises. These acts of kindness and cooperation highlight the strength of human connections and serve as a foundation for reimagining our collective response to future challenges.

However, waiting for disaster to strike before taking action has become a troubling narrative that must be resolved. Too often, leadership fails to act urgently, leaving communities vulnerable to avoidable tragedies. The time for incremental change is over; proactive, systemic adaptations are necessary to address the challenges posed by extended fire seasons and climate-induced risks.

The forecast for Los Angeles remains dry, signalling that the LA Fire Complex may not be the last blaze of the season. Yet at this moment lies an opportunity—to learn, adapt, and create a future where cities and nature coexist harmoniously. Because ultimately, this isn’t just about fires. It’s about the choices we make now that will define the landscapes and lives of tomorrow.

Local Adaptation

Integrating Indigenous Fire Management Practices: Reintroducing controlled burns guided by traditional ecological knowledge can reduce fuel loads and restore biodiversity. Indigenous practices have demonstrated success in maintaining ecological balance and mitigating catastrophic fires. While not a standalone solution, Indigenous fire management practices are essential to a comprehensive strategy to address fire risks effectively.

Enhancing Urban Planning and Zoning Laws: Communities must create defensible spaces between developed and natural areas. Limiting construction near high-risk zones and designing fire-resistant infrastructure can minimise damage during fires. This principle applies to urban settings and rural and semi-rural areas that face increasing fire risks.

Investing in Early Detection: Advanced satellite monitoring systems and drone technology can help detect ignitions early, preventing their escalation. Monitoring dryness as a primary indicator, rather than traditional seasonal calendars, can improve risk assessments and early warnings.

Ensuring Rapid Response: Rapid deployment of well-trained and adequately resourced firefighting teams is critical, especially in areas with high winds and dry fuels, where small fires can quickly spiral out of control. Effective coordination and readiness are essential for minimizing the impact of wildfires.

Promoting Community Involvement: Education initiatives led by communities and their leaders can share valuable lessons from past fire experiences. Establishing exchange mechanisms between fire-prone cities, such as Fort McMurray, and other at-risk communities can facilitate sharing best practices and steep learning curves.

Global Perspective

Involving Indigenous Knowledge Holders: It is vital to ensure that people with deep historical Indigenous fire knowledge have multiple seats at the table during global climate discussions. Their participation should go beyond studies or borrowing their practices; it must involve genuine collaboration that respects and integrates their expertise into decision-making processes where their stewardship can drive and direct.

Strengthening International Cooperation: As fire seasons increasingly overlap globally, collaboration on resource-sharing and knowledge exchange among nations can improve collective resilience to wildfire risks. However, the increasing frequency and intensity of fire seasons make traditional equipment and personnel-sharing arrangements between the northern and southern hemispheres less feasible. This highlights the urgent need for regional self-sufficiency in firefighting resources and strategies.

Addressing Climate Change: Combating the root causes of extended fire seasons requires urgent action on reducing greenhouse gas emissions and transitioning to renewable energy sources. Policies that prioritize sustainability are essential for long-term fire risk mitigation.

Developing Global Fire Management Strategies: Coordinating efforts to manage wildfires across borders, especially in regions prone to transboundary fire events, can foster unified responses and shared resources.

Fire emergencies remind us of humanity’s capacity for resilience and solidarity—stories of neighbours helping neighbours exemplify the strength of human connections. However, waiting for disaster to strike before taking action is a troubling narrative. Proactive, systemic adaptations are necessary to address extended fire seasons and climate-induced risks.

Imagine a city where trails and parks are carefully managed to reduce fire risks and communities actively participate in fire preparedness. Envision landscapes where Indigenous fire management practices—rooted in centuries of ecological knowledge—help maintain balance. This vision isn’t just about containing fires; it’s about rethinking our relationship with nature and living with fire in acknowledgement of our shared responsibility.

A.M.

Appendix 1: Impact of Major Wildfires - Within a 100-kilometre radius of Los Angeles. September 2024 - 12 January 2025

1. Airport Fire

GIS Acres Burned: 23,518.7

Start Date: Friday, 13 September 2024

End Date: Sunday, 6 October 2024.

Notable Details:

A mid-sized fire, rapidly contained within weeks.

Likely benefited from favorable conditions for firefighting.

2. Line Fire

GIS Acres Burned: 43,975.6

Start Date: Friday, 13 September 2024

End Date: Friday, 11 October 2024.

Notable Details:

A significant wildfire with fast containment progress.

Impacted areas in San Bernardino County, requiring aggressive firefighting efforts.

3. Bridge Fire

GIS Acres Burned: 56,022.3

Start Date: Tuesday, 17 September 2024

End Date: Wednesday, 30 October 2024.

Notable Details:

Among the largest fires in California during 2024.

Spanned over a month, impacting large areas near urban interfaces.

Highlights vulnerability near Mount San Antonio.

4. Mountain Fire

GIS Acres Burned: 20,630.4

Start Date: Wednesday, 13 November 2024

End Date: Thursday, 12 December 2024.

Notable Details:

A large fire with significant progress toward containment.

Spanning nearly a month, its size and duration suggest challenges related to weather or terrain.

5. Franklin Fire

GIS Acres Burned: 4,166.15

Start Date: Wednesday, 11 December 2024

End Date: Not specified, still ongoing as of last report

Notable Details:

A relatively small fire compared to others listed but with significant ongoing containment challenges.

6. Palisade Fire

GIS Acres Burned: 15,230.7

Start Date: Sunday, 5 January 2025

End Date: Thursday, 9 January 2025.

Notable Details:

Located in the Pacific Palisades region, it posed significant risks to urban fringes and conservation areas.

Burned during an unusually dry winter, emphasizing the ongoing extension of fire seasons.

Proximity to densely populated neighbourhoods heightened the urgency of evacuation efforts and firefighting operations.

7. Hurst Fire

GIS Acres Burned: 799

Start Date: Tuesday, 7 January 2025

End Date: Ongoing as of the latest reports.

Notable Details:Initiated near the I-210 Foothill Freeway and Yarnell St. in Sylmar, California.

Rapid initial spread due to high winds and dry conditions, with the fire doubling in size within minutes.

Prompted mandatory evacuation orders for areas north of the 210 Freeway.

8. Eaton Fire

GIS Acres Burned: 8,572.4

Start Date: Tuesday, 7 January 2025

End Date: Saturday, 11 January 2025.

Notable Details:

Sparked near Eaton Canyon, quickly spreading due to gusty winds and low humidity.

Highlighted challenges of firefighting in canyon terrain, where steep slopes complicated containment efforts.

Threatened recreational and residential areas, prompting widespread evacuations.

Appendix 2: Major California Wildfires Since 2000

2000s

Cedar Fire (2003): San Diego County, ~273,246 acres burned, 15 fatalities. At the time, the largest wildfire in California history.

Zaca Fire (2007): Santa Barbara and Ventura Counties, ~240,207 acres burned.

Witch Fire (2007): San Diego County, ~197,990 acres burned.

Harris Fire (2007): San Diego County, ~90,440 acres burned.

2010s

Rim Fire (2013): Stanislaus National Forest and Yosemite National Park, ~257,314 acres burned.

Valley Fire (2015): Lake, Napa, and Sonoma Counties, ~76,067 acres burned, 4 fatalities.

Soberanes Fire (2016): Monterey County, ~132,127 acres burned, costing over $260 million.

Thomas Fire (2017): Ventura and Santa Barbara Counties, ~281,893 acres burned.

Camp Fire (2018): Butte County, ~153,336 acres burned, 85 fatalities. Deadliest and most destructive wildfire in California history.

Mendocino Complex Fire (2018): Mendocino, Lake, and Colusa Counties, ~459,123 acres burned. Largest wildfire in California history at the time.

2020s

August Complex Fire (2020): Northern California, ~1,032,648 acres burned. Largest single (non-complex) wildfire in California history.

Dixie Fire (2021): Plumas, Butte, Lassen, Tehama, Shasta Counties, ~963,309 acres burned. Second-largest wildfire in California history.

Caldor Fire (2021): El Dorado County, ~221,835 acres burned.

Mosquito Fire (2022): Placer and El Dorado Counties, ~76,788 acres burned.

Key patterns show wildfires have become more frequent and severe due to climate change, prolonged droughts, and increased development in fire-prone areas. The 2020 wildfire season was exceptionally destructive, with multiple record-breaking fires.

Appendix 3: Fire Policy Adaptations

1. Greek Fires (2019): Impacting Tourist Resorts

Impact: Devastating wildfires burned through tourist resorts in Attica, Greece, causing significant loss of life and property.

Policy Changes:

Enhanced early warning systems and evacuation protocols for high-risk areas.

Stricter land-use regulations to limit development near forested zones.

Increased investment in aerial firefighting resources for remote areas.

Human Life is Priority

2. Canada’s FireSmart Program

Impact: Frequent and severe wildfires, exemplified by the Fort McMurray fire in 2016, pushed Canada toward a proactive fire management model.

Policy Changes:

Introduction of FireSmart guidelines to reduce fuel loads near homes and infrastructure.

Promotion of community-led initiatives to create defensible spaces and adopt fire-resistant materials.

Integration of Indigenous fire management practices, emphasizing controlled burns to maintain ecological balance.

These examples illustrate the critical role of adaptive policy measures in addressing wildfire risks, highlighting proactive strategies and the integration of traditional ecological knowledge.

Interesting reading!